Missionary Kids: An Anthology of Experience

Faith on the Field

No matter who you are or where you grew up, faith journeys are completely unique to every person. No one person has the same story or the same experiences. However, growing up on the mission field means experiencing God in ways most kids raised in America haven’t. Although these experiences may be different, their paths aren’t so different from the path of someone who grew up in the United States when it comes down to the brass tacks. In order to gain some insight, MKs (Missionary Kids) from North Central University were asked to describe their faith journey and how it evolved as they grew up on the mission field.

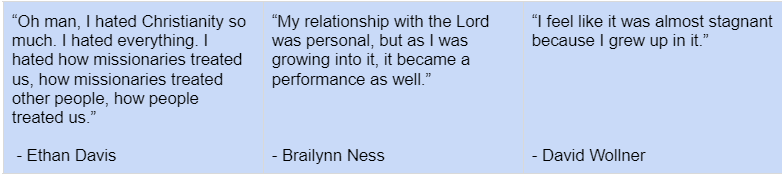

What did your Faith look like while growing up on the mission field?

Each answer was completely different and complex in its own way, but if you break them down and go more in depth, you can probably connect to one of them.

In her answer, Brailynn Ness, a 23-year-old MK from Africa, elaborated by saying that, “There were a lot of hard things about being a missionary kid because I felt a lot of pressure to perform and to please the missionaries that were around me.” Her experience began as a performance of her faith, and pressure to seem like the perfect, poster child for missionary kids. She goes on to say, upon returning to America, her family stepped out of the mission field. “It was during that time that my faith began to not be so much about performance, and the Lord began to break that down in me,” Ness said. “I don’t care about performing anymore and it’s a lot more intimate of a relationship.” This ‘poster child’ pressure and ideology are often seen with pastor’s kids or even children of people who are incredibly involved in their church community.

In her answer, Brailynn Ness, a 23-year-old MK from Africa, elaborated by saying that, “There were a lot of hard things about being a missionary kid because I felt a lot of pressure to perform and to please the missionaries that were around me.” Her experience began as a performance of her faith, and pressure to seem like the perfect, poster child for missionary kids. She goes on to say, upon returning to America, her family stepped out of the mission field. “It was during that time that my faith began to not be so much about performance, and the Lord began to break that down in me,” Ness said. “I don’t care about performing anymore and it’s a lot more intimate of a relationship.” This ‘poster child’ pressure and ideology are often seen with pastor’s kids or even children of people who are incredibly involved in their church community.

On the other hand, Ethan Davis, a 20-year-old MK from Africa, describes an almost resentful beginning. “I just did not like Christianity at all, mainly because I grew up going to church. We didn’t have Sunday school most of the time so I would just sit and listen to my dad speak about biblical principles,” Davis said. “I’d look around me and apply these principles to missionaries who were supposed to come and live them out among people without question, without being rude, or mean, or putting each other down. All I saw was the exact opposite: people putting each other down, people being rude, and so on. I thought, ‘these principles must not be working,’ and I hated it. I hated the hypocrisy.”

On the other hand, Ethan Davis, a 20-year-old MK from Africa, describes an almost resentful beginning. “I just did not like Christianity at all, mainly because I grew up going to church. We didn’t have Sunday school most of the time so I would just sit and listen to my dad speak about biblical principles,” Davis said. “I’d look around me and apply these principles to missionaries who were supposed to come and live them out among people without question, without being rude, or mean, or putting each other down. All I saw was the exact opposite: people putting each other down, people being rude, and so on. I thought, ‘these principles must not be working,’ and I hated it. I hated the hypocrisy.”

This is where you can begin to bridge the gap. Many people in America have disdain for Christianity because of the way Christians seem to contradict their own beliefs. Church hurt and hypocrisy is its own pandemic within our faith and those who experience it are in a similar position to Davis. However, this resentment changed for him in the tenth grade. “I just got tired of everything. I decided that perhaps I had focused too much on the bad rather than focusing on the good and what could be,” he said. “I realized that, as humans, we are sinful and we can’t be perfect. We’re not supposed to live up to these biblical principles; we’re supposed to reach there in time.” Both of these people experienced a growth moment and it affected their faith for the rest of their lives.

David Wollner, an 18-year-old from Indonesia, had a different perspective than the other two. He believed that his faith was fairly stagnant for most of his life. In his interview, Wollner stated, “It’s always hard because you see these people who come to Christ and experience this great change in their life and it keeps this fervor going, but I never really had that. Because I followed Christ so early, my whole life it felt almost as if it was just nature to do so.” He continued down a similar path that Davis did, finding his spark in his junior year of high school. “In tenth grade was when it really started to spike,” Wollner recalled, “and I decided I was serious about this, because I saw my first miracle.” Overall, this is an experience that many Christians can relate to regardless of where they are. Starting out with following the status quo of our culture, or we don’t know Christ. Then, due to one thing or another something miraculous happens to change our point of view.

David Wollner, an 18-year-old from Indonesia, had a different perspective than the other two. He believed that his faith was fairly stagnant for most of his life. In his interview, Wollner stated, “It’s always hard because you see these people who come to Christ and experience this great change in their life and it keeps this fervor going, but I never really had that. Because I followed Christ so early, my whole life it felt almost as if it was just nature to do so.” He continued down a similar path that Davis did, finding his spark in his junior year of high school. “In tenth grade was when it really started to spike,” Wollner recalled, “and I decided I was serious about this, because I saw my first miracle.” Overall, this is an experience that many Christians can relate to regardless of where they are. Starting out with following the status quo of our culture, or we don’t know Christ. Then, due to one thing or another something miraculous happens to change our point of view.

Crafted in Culture

What are some things that come to mind when you think of American culture? There are several stereotypes of culture that are associated with the American way of life:

- Hamburgers, hotdogs, and potato chips

- Classic American football, or a baseball game (complete with a bag of peanuts, of course)

- Country music or Rock n’ Roll

We tend to look at other countries’ traditions and cultures and find them strange, odd, or weird compared to our own; however, the same is true on the flip side, and this is exactly what Missionary Kids feel when returning to the states after growing up on the field.

Dale Hawley, in his article “Research on Missionary Kids and Families: A Critical Review“ from the Mission Resource Network, states that “growing up in another culture is a lifelong influence for most MKs.” Many MKs find that, upon returning to the United States, they have picked up characteristics and traits from their host country.

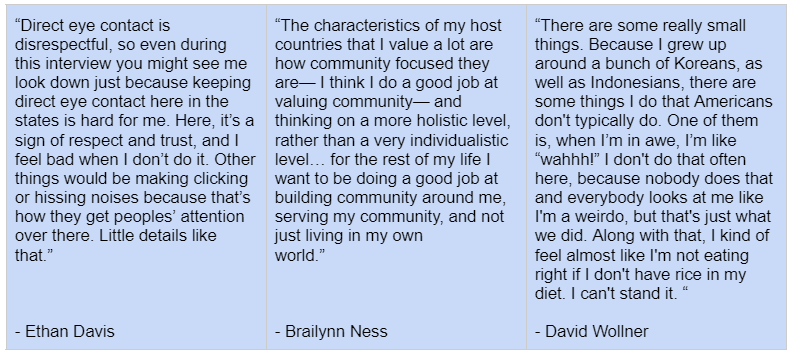

What characteristics of your host country’s culture have become a part of you?

Each person that was interviewed grew up in a different part of the world, and they were all affected by the cultures they experienced. Ethan Davis, an MK from Senegal, put it this way: “The culture I grew up with over there was all I knew. I spent way more time over there than I did in the states… Senegal is all I’ve known socially, verbally and so on.” Many MKs experience a similar situation and find that they have assimilated traits from their host country’s culture, as seen above. These three individuals, even though they all grew up in different areas of the world, can be seen to have both similarities and differences. Davis and Wollner both detailed things that might make them seem odd or strange, yet are completely normal in the cultures of their respective mission fields. Ness shared the value of community and how that carried over throughout all of the cultures she lived in. These traits seep into everyday life and many kids who return to the states find that the culture here is significantly different from the one they grew up in. Each person has their own specific experiences, but all are similar in that they are important to each individual because of the fact that it’s how they grew up. Many find a nostalgic comfort in these aspects of life and only realize that these traits differ from Americans when they return to the states.

Returning to the States

‘Reverse culture shock’ is a term that goes hand in hand with MK’s and their unique experiences with culture. The U.S. Department of State describes reverse culture shock as when people who had been immersed in a foreign culture for an extended period of time “expect their home to be just the same as it was when they left. While [they] were outside the country, events and new developments, however, have changed the fabric of [their] old community. These natural changes can be shocking and disorienting upon return.” Many missionary families struggle with repatriation, or returning to their home country, because of this. However, many MKs do not necessarily view returning to the United States as ‘returning home,’ especially those like Davis who lived there for their entire lives. When the anonymous volunteer was asked how he believed raising his children on the mission field affected them, he said, “One thing I’ve always wondered is if coming back to the U.S. and realizing it requires some amount of culture learning and relearning diminishes the idea that America is their home country.” He then went on to add, “for my part, every few years I’m on the field and then come back to the U.S., everything changes; people change, culture changes… every time I came back, it had changed more, and at some point ten years ago, I thought, ‘maybe this isn’t who we are anymore.’”

Home is where the Heart is

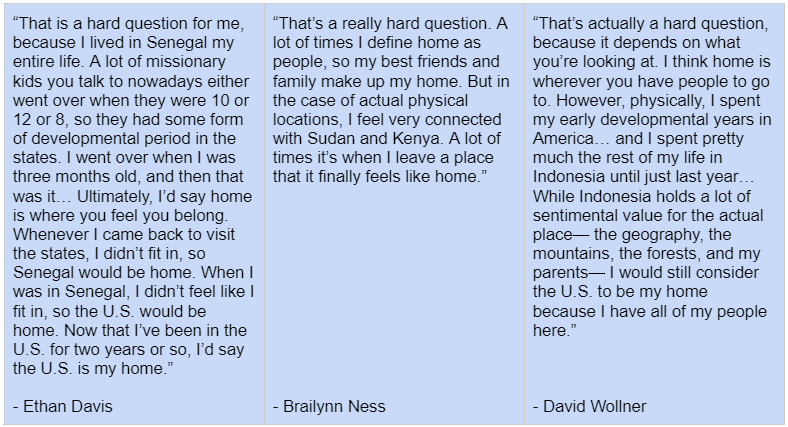

What is home?

Many MKs return to the states during their teenage years to go to school, and eventually, they stop returning to their host country altogether as they begin to pursue higher education. During each interview, when asked the question “Where do you consider home to be?” Each person paused and then gave a variation of the statement, “that’s a hard question.” Home is a complex and ever-changing definition for MKs because of how often they move around.

Throughout these answers you can see that a sense of belonging is a common theme. Belonging is important to everyone, especially during formative years when kids seek friends and to connect with a community. Making friends as a missionary kid is incredibly difficult. Here in the states, kids often go through grade school and high school with the same people. They can keep friends for years and interact with the same peers throughout their school careers. However, MKs have an ever-changing lifestyle, with moving on and off the mission field, that keeping friends is hard, and saying goodbye is harder.

Goodbyes

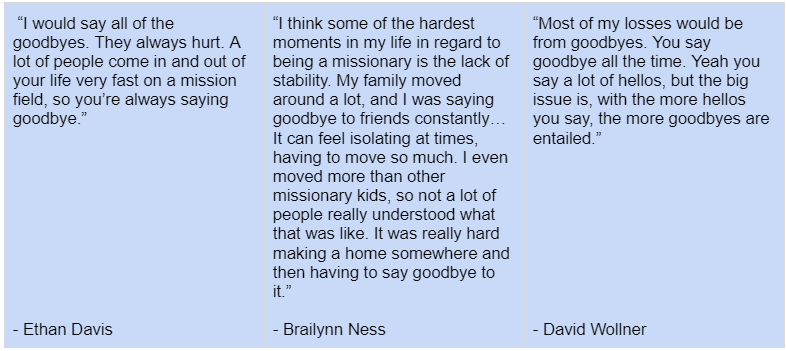

In order to gauge how their experiences shaped how they interacted with the world around them, each interviewee was asked what their greatest victories and deepest losses were. Each person had a different victory; Davis enjoyed helping others, Ness was overjoyed at seeing how God was using her to help others and Wollner talked about miracles. What was shocking, however, was their answer to the second question regarding loss. They all said the same thing.

Goodbye is always a hard thing to say, but in the states, it is simply a parting message. Overseas, on the mission field, it holds a completely different connotation. For MKs, when they say goodbye, they never really know if they’ll ever speak to that person again. Making significant connections is difficult because of the distance, constant moving and culture barriers. This can be, as Ness stated, very isolating for kids as they grow up. As adults, they tend to expect loss in their lives and are afraid to seek out close and impactful relationships. When they repatriate to the states, they need to relearn what forming a relationship with someone is like, without needing to fear that they will leave and never return. College provides a lot of MKs with those opportunities for relearning. When saying goodbye becomes as common as saying hello, a lot of MKs bond over and understand that friendships and relationships might not be permanent. They learn to live in the moment and appreciate what they have now, rather than worry about the future.

NCU's Spring Writing for Media class investigated what it's really like to be an MK.